This the third in a three-part series of articles about dealing with fear:

Part 1: Three great ways to fail miserably

Part 2: Fail, change your approach, succeed

Part 3: Fail, but find a new direction

Some years ago, I went through a series of failed attempts to get promoted.

I’m a big believer in using data and information to help you, but in this case I came out of a succession of promotion interviews with nothing more useful than a ‘bad luck’ and just having apparently lost out to a better candidate. What I wanted was some actionable feedback I could work on to give myself a better chance next time.

I went through an inevitable period of feeling sorry for myself – there’s nothing wrong with this, and it can be an important part of the process of coming to terms with a failure (or string of failures) as long as you don’t wallow in self-pity for too long.

At some point you need to get up and move on. And in blaming the lack of feedback, the lack of luck, I completely failed to take any responsibility for what had happened.

After six failed promotion attempts, I attempted to move on. I decided that the role I was in was a good one and that actually, staying at that level would mean becoming more of an expert in that area, which was an interesting one. I would also have the physical and mental capacity to do far more outside work.

But I couldn’t shake the frustration, the feeling that I was being under-valued. Did I mention that I wallowed for a while?

The problem with going for promotion, or any big job, is that it is, and should be, an intense and draining experience. The notion of casually ‘throwing your hat into the ring’ is nonsense – if you want to have a serious chance of getting the job you want, you need to commit to what you’re applying for. You need to really think yourself into the job, imagine yourself running that area, managing those people, being that expert or leader.

If you go into a job application half-arsed, it will show, and the recruiting team won’t want to hire you. You need to show that you really want the role and that you’ve done the work to understand what it will take to do it well.

But that’s exhausting, and if you go through this process a few times (each of which probably lasts a few months) it’s easy to get disillusioned with it all. Because however well-motivated you are, however good you are at dusting yourself down and going again, after a certain point you might feel like you’re wasting your time.

The effort has to be worth the perceived reward at the end of it. The strain and stress has to be for something.

Sometimes you can just get to the point where you have learnt and re-tried all the things you can, and it still doesn’t work.

The more you fail, the more it needs to mean to you, in order for you to summon the resolve to have another go; and that… after a certain point it’s not worth it (or it might feel that way to you)

That’s the point at which the real opportunity presents itself – what do you really want? What do you really need to do to make it happen? Or is there something else that this is showing you that you couldn’t see before?

Ultimately, the biggest fails can be the most rewarding, because they enable you, and force you, to look at your direction, and work out if there is a better way. They can also force you to look at the really hard questions – what if I never get there? What if this never works? What’s the plan then?

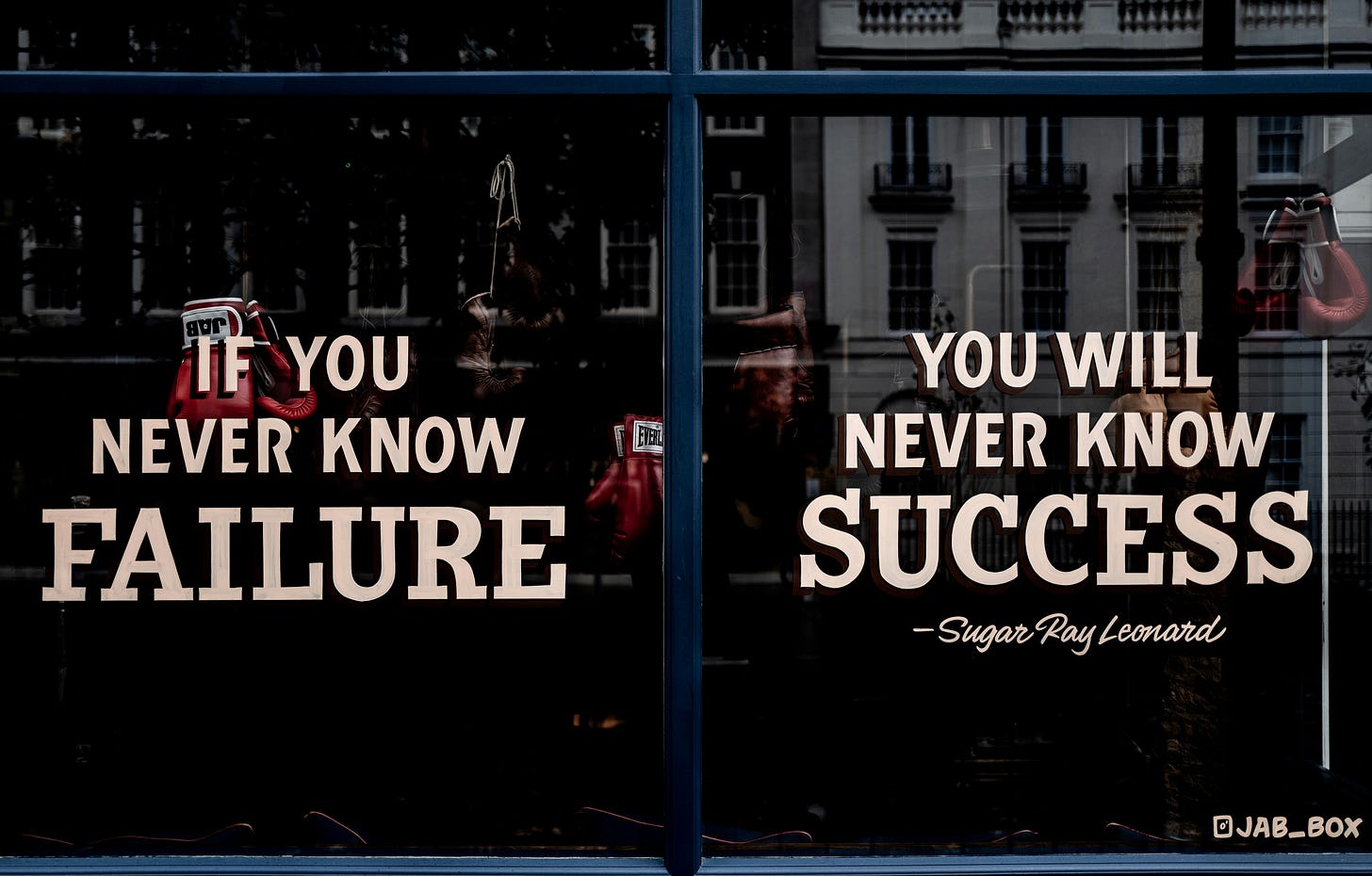

I started this week’s series of blogs by talking about how important it is to fail. And the most important reason may well be that it enables you to look at your life and give yourself the courage to make real change. Realistically, you will never do that if everything is going well, or if it’s still just about bearable.

If there is no ‘burning platform’, if everything is just good enough, then why would you jump?

Only by failing (perhaps spectacularly) do you get to see the real, radical alternatives. Only by failing are you forced to hold a mirror up to yourself and think whether there’s a better way, whether you have the will to keep banging your head against this particular brick wall or whether there is a better, more productive, more fulfilling use for your time and energy.

And this isn’t about giving up – this is about understanding that you have a finite amount of time and energy, and making clear, conscious decisions about how you can best spend. It you’re not pursuing the goal you thought you were, what goals are you going to pursue instead?

And sitting on the sofa eating Doritos isn’t a goal.

Failure is inevitable, but failing to achieve what you want in life is not. You should hope for the best, believe you can get there and give your best effort to the things you want to achieve. But occasionally you might feel like you’ve reached the end of that particular road. And that’s when you can really ask yourself ‘what next?’

And that’s not a failure, it’s a new opportunity. Because all of the assumptions you had about what your life or direction consisted of are there to be questioned, to be challenged, to be broken down.

You are no longer encumbered or restricted by the guardrails you thought you had before. That other path isn’t open, so that means you’re free to do something different. And maybe you need to, if your current path is costing you emotionally, financially and in morale and motivation.

Even the most insoluble failure can show you another way. And that way would not have been visible to you if you had got what you originally wanted (or thought you wanted).

Making that shift, that jump, is really hard. It’s probably a big decision.

Many of us will keep hammering away because we’ve already invested so much time/effort/money – I’m throwing all of that away if I give up now. This is the Sunk Cost Fallacy, whereby we keep doing the same thing because we can’t stand to accept the loss of what’s already been invested.

But that fails to understand the opportunity cost – how else could you be spending all the time and energy that you still have to give? What else could you be achieving?

The questions to ask yourself in this situation are:

Have I given this a fair go? In five or ten years’ time, will I think that I tried hard enough?

Has the journey given me enough already that I will look back on?

If I was to do this for another 1/2/3 years, and made it, would that still be worth it?

If I was to do this for 1/2/3 years and didn’t make it, would that feel like time well spent?

How else could I be spending that time – what other goals could I be pursuing?

Have I learnt enough, that I could use somewhere else?

I’m not someone who believes that ‘everything happens for a reason’. I’m much more in the camp of ‘a bunch of stuff happens and you need to deal with it’. Sometimes things just happen. But those things can open doors as well as close them.

There are an infinite number of paths available to you – all of those contain opportunities, and pitfalls.

Ultimately, every failure you encounter and endure is something you can use, and ‘learning from failure’ doesn’t mean ploughing the same furrow until you die or go mad from the frustration. Learning from failure means:

Getting better at the thing you’re doing

Achieving the same goal but in a different way

Find a new and more fulfilling direction for your time, energy and life

And they all sound better to me than ‘failing’.