Vicarious adventures

Why risk your life when you can read about other people risking theirs?

There’s something about this time of year that makes me reach for the mountaineering stories. At the moment I have on the ‘next to read’ pile ‘The Wild Within’ by the excellent Simon Yates (the other end of the rope of Joe Simpson’s Touching the Void story), and Fergus Fleming’s classic Alpine history Killing Dragons. The latter might be my most re-read book, a wonderfully entertaining account of the early years of mountain exploration in Europe.

During Covid we also discovered the joys of the Banff virtual Mountain Festival. The actual festival takes paces each year in Banff, Canada, and is a celebration of the best adventure-themed films to have been released over the past year or so. The themes cover extreme skiing, exploration, ecology and anything to do with experiencing the world’s wild places.

Each year a selection of films are curated and taken on tour, to be shown in local theatres around the world. I started taking the kids to these in around 2018 – it’s a fantastic evening of escapism, inspiration and bucket list creation.

Then Covid happened and the enterprising people at Banff put their best films online, so you can have an evening of mountain exploration in your own home (which has the added bonus that you can go for a wee whenever you want. You can also buy gift cards for the online show so they make a great present for anyone with a winter birthday.

Watching and reading about these terrifying adventures has a number of benefits. Of course there’s the awe and inspiration of what humans have been able to achieve, from the adversity they’ve overcome, to the noble and tragic ends of so many people chasing their dreams. Banff in particular gives some wonderful insights into places I might not otherwise have considered going.

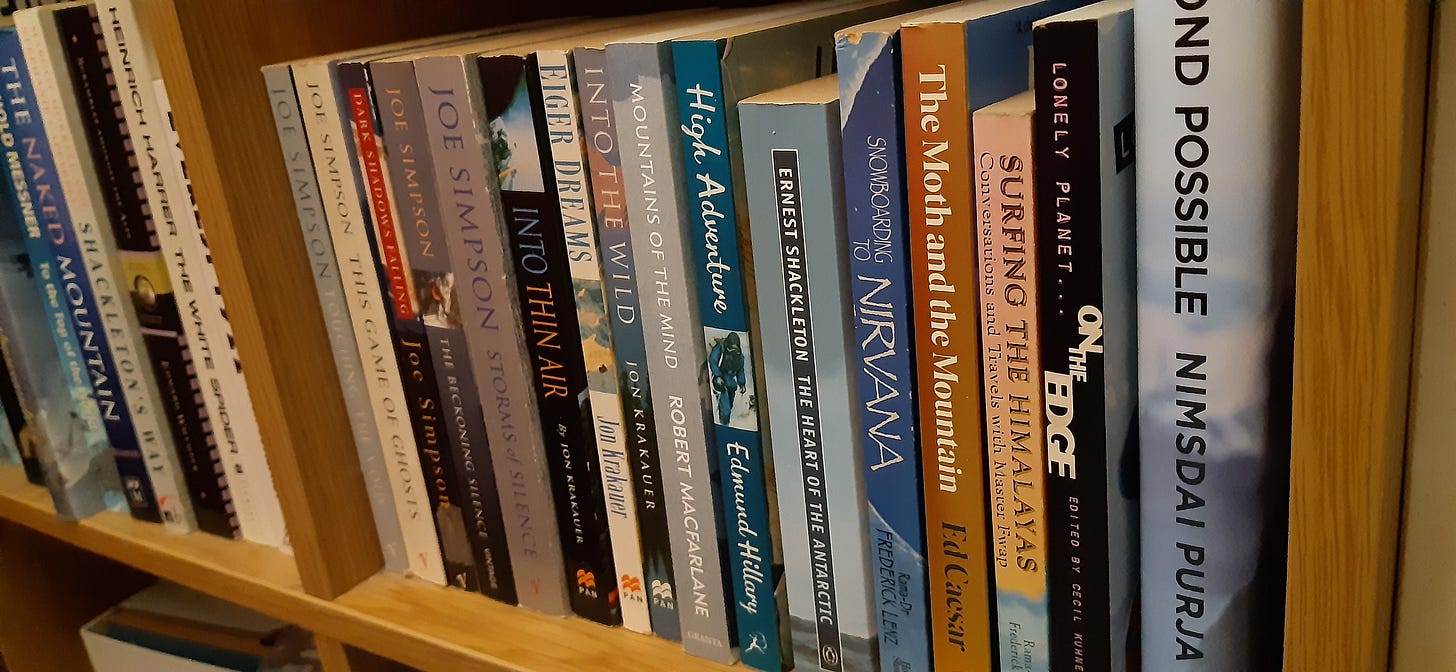

But these tales and travelogues have been just as useful in framing what I definitely don’t want to do. When I read the first of the thirty-odd books I have covering Himalayan mountaineering I was awestruck, while being absolutely certain that I didn’t want to ever do that myself. But I still kept reading the books, loving the adventure stories and the tales of hardship and ambitions dashed and achieved. And I loved the feeling that those mountains, avalanches, crevasses and storms couldn’t ‘get me’.

I did dabble with mountain sports a fair bit when I was younger – regular snowboarding holidays soon left the pistes and became weeks of backcountry exploration, of understanding the mountains, of escaping the crowds to find your own piece of real alpine peace.

A top British snowboarder called Neil McNab used to run Kommunity Snowboarding camps (maybe he still does), in which soft city folk could go to Chamonix, the centre of mountain sports in Europe and the place where mountaineering started, and experience ‘real’ snowboarding – the kind where you hike for three hours into the backcountry and rappel down a couloir to find the best untracked powder. We might only actually ride for 15 minutes in a day, but it would be the best 15 minutes ever – soft, waist-deep snow, the whole slope to yourself, first tracks, wonderful.

This certainly taught me about appreciating quality over quantity in the mountains, at a time when most skiing holidays were about being on the first lift up, riding hard all day, last lift up then straight to the bar. Repeat until broken. I get tired just thinking about it now. But the McNab ethos was different, it was about finding the best that the mountains had to offer, while appreciating the dangers.

We learned avalanche safety and crevasse rescue. My friend fell into a crevasse and we fished him out. We learned to take climbing kit with us even if we weren’t climbing. We learned that one descent a day can be fine (and he was right, I still remember those descents more than any others). We got away from the crowds and found peace, even in an otherwise crowded resort. I may have hugged a tree at one point.

These Alpine holidays culminated in an organised trip to climb Mont Blanc in 2006. To be clear, this was essentially booking a holiday – although Mont Blanc is the biggest mountain in western Europe at 4808m, the climb itself is really just a long hike. It’s high enough that you can experience the effects of altitude and it’s certainly a long enough trek that you need to have trained for it, but there is little in the way of technical climbing – a couple of hours scrambling at one point but otherwise it’s walking uphill in deep snow for a long time.

Inevitably, the dozen of us that made it to the summit were soon talking about what was next, having spent much of the week sharing how we’d got here and what led us to take a week out of our lives to come here. And the guides, not wanting to miss a sales opportunity, were keen to tell us what was available.

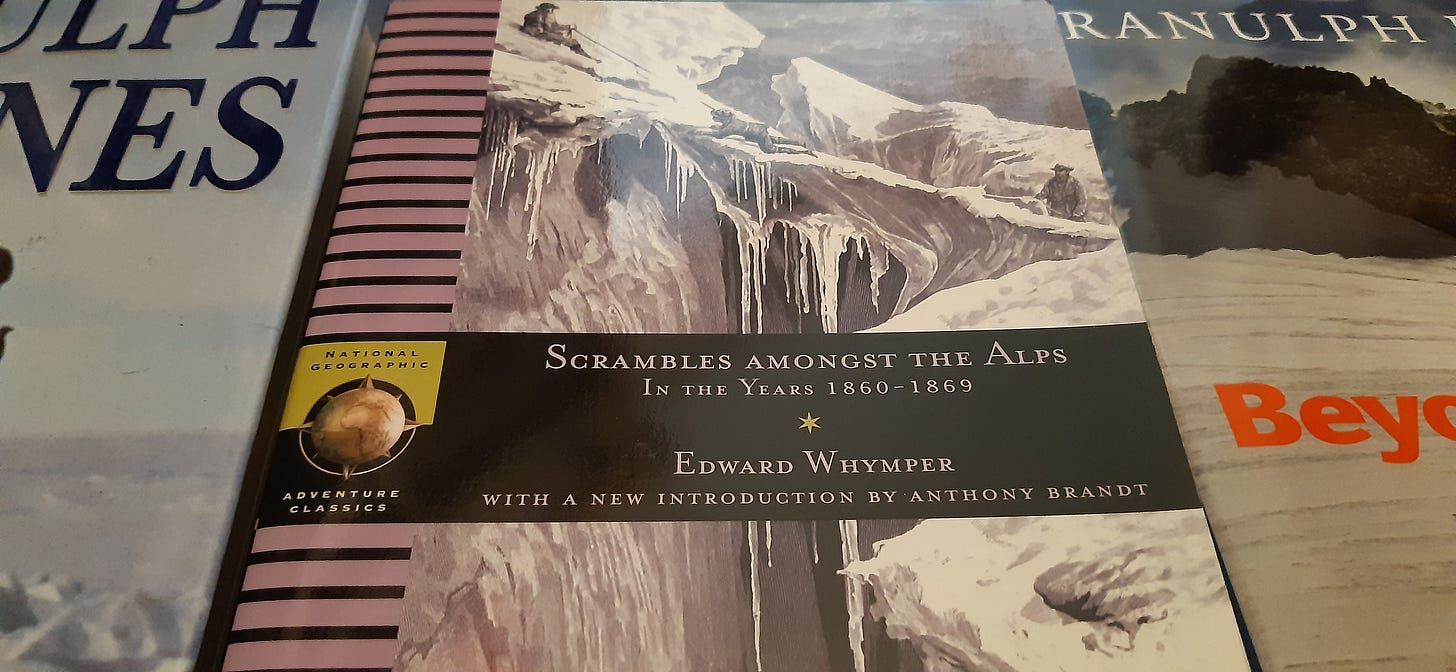

It seemed that scaling the Matterhorn was the logical next step – not quite as high as Mont Blanc but a more technical climb and something that would give more of a feel for real alpine exploration. I wasn’t convinced, having read Edward Whymper’s account of his first attempts on Matterhorn in the 1860s, several of his party being swept from the mountain to their deaths by a freak storm in an incident that briefly paused the frantic rush to scale the most iconic European peaks.

Matterhorn was for many years considered unclimbable. Yet now we were being invited to book a holiday to get to the peak ourselves. And whereas it was previously a several-day expedition, climbers in the last ten years have made it to the peak in under two hours – and even getting from Zermatt to the peak and back again in under four.

But it’s still a mountain that many people have died on. And from a domestic perspective, I’ve skied and snowboarded enough mountains to know a slippery slope when I see one. This, exciting as it sounded, had all the hallmarks of being the thin end of a very large wedge. If I signed up for this, I would be embarking on a decade of mountain adventures.

And of course there’s nothing wrong with that, but there will always be another goal, a greater challenge, something else to tempt you in a new and interesting direction. Or to your untimely demise…

In 2003, on McNab’s Kommunity snowboard camp level 3, we were getting ourselves into some serious situations (and sometimes putting ourselves into them deliberately to learn how to deal with them). We triggered small avalanches to feel what moving snow is like under your board. We buried each other in the snow to practice quick and effective use of transceivers (you don’t want to get that one wrong). And there was one hair-raising descent off the back of Flegere, down a 50 degree slope that allowed just one turn in each direction before you reached the foot of the slope. It was high-speed, full commitment, heart-stopping riding.

And there was a point, just before or just after those two eye-watering turns, that I thought ‘do you know what, I’m not sure I want to do anything more challenging than this’.

It was an incredible experience and an incredible week. But it’s a matter of what’s enough – when have you gone far enough down a different path? When do the returns start to diminish, so that you’re just doing more of the same instead of something new and exciting? Or when are you just being plain silly and putting your precious life at risk?

Twenty years on, I’m happy with the decision to stop after Mont Blanc. I get just as much out of climbing in the Lake District with the family, or running over the local hills here in central England, as I did from those bigger adventures. But I’m really glad I did them.

It’s important to find your own level of adventure, the one that’s right for you, and be content to live the rest vicariously. I’m very happy to read about attempts on K2, Nanga Parbat and Kangchenjunga without feeling the need to have a go myself. But having dipped a modest toe into those adventures, having experienced my own tiny version of them, enables me to appreciate so much more the heroic, hair-raising exploits of pioneering mountaineers, explorers, and all those who weren’t prepared to entertain the idea that ‘it can’t be done’.

It’s also why, these days, I ski rather than snowboard. I’m less competent on skis, but that means I learn more and it feels newer. Skiing is something I do with my family – snowboarding was something I did with my friends.

And every adventure, every trip has been a step along a long and winding path that has led me all over the world, has led me to love the outdoors and the mountains in particular, and which I hope has led to my kids being able to appreciate some of the same things that I’ve been lucky enough to experience. I doubt I’ll scale any major peaks again, although you never know, I might have another mid-life crisis in me yet.

We’ll be back in the mountains at some point this spring, messing about on the lower slopes, experiencing some mild peril and building another layer of memories and appreciation of these wonderful environments.

Sometimes, vicarious adventures can be the best ones.