Klaus turned and showed me his hands, great meaty shovels, every finger on which had been broken numerous times. “You don’t really work here until all your fingers have been broken in the press”, he grinned.

Klaus was not the exception – everyone I had met so far had huge yet mis-shapen hands, usually from many years of working in this place where I was very much the new boy.

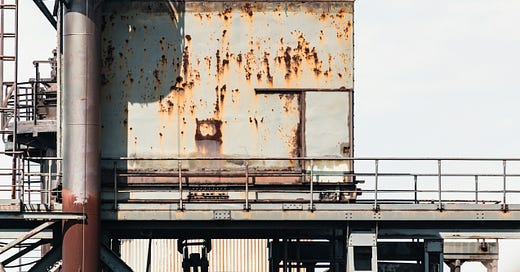

This was day two in the sheet metal factory in Dinslaken, a small industrial town forming part of the grey Rhineland sprawl across Western Germany, including Dusseldorf, Essen, Dortmund and Paderborn. My first job abroad, I had been lucky enough to secure three weeks here before returning to University at the end of the stint.

Although I had always taken a very open-minded approach to summer work, I had struggled this summer in the early ‘90s – the usual waiter and agency gigs I lived off seemed to have dried up, and I had had to ask my Dad to see if any of his contacts could offer me some work. And he had come up trumps – firstly getting me four weeks running a summer playscheme in a terrible part of the West Midlands of England, and then secondly landing work through an old friend in Germany, who happened to be high-up in Personnel for Thyssen Bausysteme, the European steel titan.

To my young eyes, this work was extraordinarily well-paid, and I soon came to suspect that there was a danger money element to this. I was earning around 8 pounds an hour, which was more than double what I had got for previous factory or warehouse-based jobs in England. As a non-resident student, I was also able to reclaim all the tax I paid, which provided a further windfall a few months later.

But there was certainly mild peril. The work was simple – with your working partner, pick up a large steel sheet, push it a certain distance into a giant industrial press. Press a button, which folded the sheet in a certain way, then take the sheet out again. Flip it over, repeat until the big bell rings in eight hours’ time.

The work was exhausting and mind-numbingly boring. Pick up the sheet, press the sheet, remove the sheet. All day long. We’re often told today how we should let our kids be bored as it’s good for them, and this job taught me the good sense behind that. I learnt how to deal with the lack of stimulation, to keep focus as well as gaining a huge amount of appreciation for my life situation and that, hopefully, all being well, I wouldn’t spend my life doing this.

British Forces radio played loudly at all times and this was a godsend. I occupied the rest of my mental capacity trying to make a game out of the work we did. How many sheets per hour; what percent of my student loan was I paying off, how many fingers I still had.

It was a difficult blend of being incredibly boring while also not allowing you to switch off – mis-pressed sheets came out of your wages and you were only ever therefore a few seconds of mind-wandering away from a set of mangled digits.

The monotony of the day was punctuated only by sausages. Several times a day a sausage man would come onto the factory floor, bearing large bratwursts, bread and mustard. The workers flocked to the Wurstler like seagulls on chips.

I’m not a large man, but in just three weeks I put on nearly two stone (15kg), by virtue of ingesting only sausage, bread and beer, and spending eight hours a day lifting steel sheets. The weight fell off again just as quickly when I returned to my scrawny and sedentary lifestyle back in the UK.

I was staying with a local family, several of whom worked at the factory themselves and who viewed the HR department with deep suspicion following some union row – as such, there was a non-zero chance in their eyes that I was a HR mole, planted as a cunning ruse to find out what the proletariat were really thinking.

The family were wonderful, once their suspicion of me had subsided – every morning the Mum made sandwiches and coffee for me and left out breakfast (as I had to leave the house at 5.30 am). Reiner (the younger son, in his mid-20s) and I went to nearby woods for a run (like many Germans I subsequently met, he didn’t seem to do much exercise yet was ridiculously and effortlessly fit).

One evening we watched a Bundeliga game in a nearby bar – Borussia Dortmund against some team from the south, possibly 1860 Munchen. It was much the same as going to the pub in England, only with actual conversations about real issues. All the young people seemed incredibly well-informed about topics like global politics and the environment. I could talk credibly about pop music and English football but probably not much else. Certainly not the news. I could sense their disappointment as I failed to name British Cabinet Ministers and their key policies. And it seemed like my co-drinkers actually found this stuff out for fun. Learning stuff at home? What’s that about?

It was also on this trip that I discovered the phenomenon of the German un-joke. Here’s an example that had half the pub falling about in laughter:

Kommt der Mann aus der Kneipe – und er Bus ist weg

(A man comes out of the pub, and the bus has gone)

No, that’s the whole joke. Those crazy Germans.

On one of the weekends, Reiner and his friend were heading to the opening of another friend’s new bar near Jena, across in what had only recently stopped being East Germany.

Essentially the friend was having two opening events – one for friends only on the Friday night, then an official opening to customers on the Saturday. We would go to the first, which Reiner had warned me would be more than enough. He wasn’t wrong – we didn’t have to pay for a drink all night, as the new proprietor proudly shared his wide range of beer and schapps with us all.

There’s something about having had a couple of drinks that makes speaking a foreign language much, much easier. A lot of it is just the confidence to have a go and to not worry about making mistakes, but it’s more than that – two or three beers in and it genuinely feels like you can bring the right words to the front of your mind, that you can form long, fluent sentences without having to think particularly hard about what you’re trying to say.

Whatever it is, it works, and I found myself chatting to a range of locals, to the bar owner himself, to various girls from the nearby village that had come along to make up the numbers. I’m sure the sentences I was coming out with were barely coherent, but I felt like I was holding court - and there was something of genuine novelty as they didn’t get too many English visitors in that part of East Germany.

The evening continued until about a dozen of us were sat along the bar, being served shots of schnapps, which we were invited to blind-test and identify the flavour. To me, they all tasted like different varieties of petrol and paint-stripper, but the others confidently called out ‘Raspberry! Plum!’ as though we were at an ice-cream parlour.

I woke up later, face stuck to the bar – just one or two others were still awake and nursing a last drink. Most others were in various horizontal states, either on the floor or folded in strange positions on or near the bar.

I woke up again some hours later, now somehow on a rollmat in a back room, lined up like sardines with most of the others.

Thank goodness I didn’t have to drive back to Dinslaken. Reiner once again stepped up and got us all home safely while I did my best impression of a snoring, farting labrador in the back. Thankfully, hangovers back then lasted hours rather than days so it was up early and back to the routine the next day.

Back at the factory, the workers did get coffee breaks, during which time they played the baffling card game of Skat. Actually, it’s a perfectly straightforward card game, unless you’re watching it played, in a language you don’t understand that well, with no-one having explained it.

From what I could gather, these were the rules:

Play a random card into the middle

Shout out a random even number

One random player would then fall about, laughing and pointing. One person would give another person a couple of coins, call the first person something very rude, then it all started again.

But no-one was going to waste their precious break time teaching a new person (fair enough), so I watched, guessed what was happening and joined in the laughter when someone had done something foolish.

I left and returned home and to University at the end of the summer, heavier, stronger, richer and having picked up a number of interesting German idioms that I would confuse my language tutors with that term. And my dainty little fingers remained intact.

Verdict: An interesting insight into real, industrial Germany with a decent safety net attached. I’ve not been back to that area since and have felt no draw towards it (having subsequently discovered Bavaria, which is both more beautiful and much more weird). More on that some other time.

But I did conclude that spending a few weeks doing proper graft in a proper factory should be compulsory for all young men (perhaps as an alternative to the often-touted conscription). Early starts, hard work, beer and sausage and what was for me a first chance to see a foreign language used in its native environment, not a text book.

And I’ve never looked at a steel sheet quite the same since.