It’s about 1989. School is done for the day and I wander the 20 minutes into town to one of my favourite places in the world – HMV. This music shop, a stalwart of British retail for many decades, is still going, somehow, in spite of several buy-outs, reinventions and the general decline of the economy and the British High Street.

Other record shops were available of course – Our Price, WHSmith and Woolworths all had a place in my heart, and where I grew up in Coventry there were a couple of proper, independent record shops, filled with intimidatingly cool people with earrings and tattoos. Playing bands that shouted instead of singing, and who wrote songs with titles the shop had to put a sticker over.

But at heart I was fairly mainstream, so HMV was my second home and I would probably go twice a week – often to browse, sometimes to buy. On Monday it was new releases; at other times I would gravitate to the alphabetical section to see if they had got any new back-catalogue gems from my favourite artists – at the time this was New Order, Erasure, Depeche Mode. If I was pretending to be cool, Sisters of Mercy. If not, whatever was in the charts.

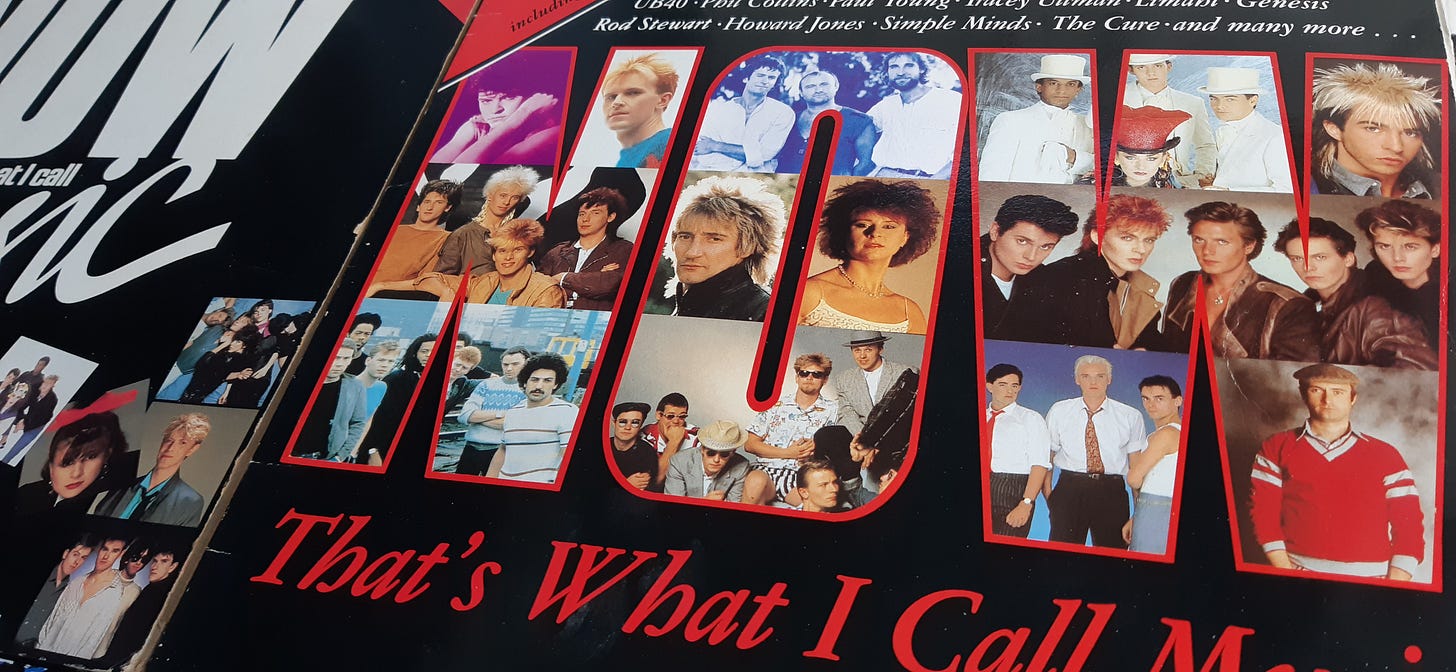

It’s hard to explain to someone today (and I know this because I’ve tried to explain it to my children on many occasions) how big a deal the charts were in the 1980s. The week’s Top 40 singles list was the undisputed, authoritative account of what was hot and what was not. Having the highest new entry or highest climber was a major accolade for a band and would mean you were a big talking point in the playground and on the street.

Having an actual number 1 hit was the pinnacle – and at the time it was a genuine measure of success. We still have the charts today of course – the weekly UK Top 40 is as much a weekly fixture as it ever was. The difference back then, before songs on adverts, viral hits and Ed Sheeran each respectively broke the charts in their own way, was that in order to achieve a million-seller, a million actual humans had to physically go to an actual shop and pick up an actual copy of your latest single.

That not to belittle today’s equivalent, which I believe requires you to have amassed 200 million streams and is clearly no mean feat, but I’m sure the idea of a million fellow citizens going to the shop to buy your music must have given a warmer glow than streaming ever could.

And so, whatever was hot, the walk to and from HMV was a real treat – anticipation on the way there; guilt and anticipation on the way back, knowing you were just minutes away from playing your new purchase on repeat until your exasperated parents asked whether you didn’t have anything else you could play…?

So much of the joy of this experience came from the scarcity – both of finding the thing you wanted in the shop (which was far from certain), and of the lack of money meaning at best I could buy a single once in a few weeks, or an album once in a few months, if I bought nothing else.

If you’d have offered me the entire world’s music back then, in a device in my hand, I wouldn’t have known what to do with it, but I probably wouldn’t have ever left the house again. This does feel like a common nature of life today – we’re faced with the entirety of the world’s knowledge, art, music, opinions, and we don’t know where to start in wading through it. So instead we waste our time looking at garbage.

Today, I could learn anything I want, in any order, from beginning to end and probably for free, but I don’t and while I’m not particularly one for spending hours scrolling on social media, I’m as prone to distraction as the next person.

In one of his recent Modern Wisdom podcasts, Chris Williamson likened this to Caesar being offered the Great Library of Alexandria, the home of all the world’s knowledge and wisdom at the time, but being perpetually distracted on his way to the Library by a fight in the chariot park, or an interesting animal that happened to wander by.

As with many things, there’s a point where an amount of choice becomes unhelpful. In Italy last summer, we came across a gelateria that boasted 150 flavours. Myself, my wife and children were immediately paralysed by indecision. 150 flavours, two scoops to a gelato, that’s like, erm, loads of flavours.

My son regressed and went for chocolate. I panicked and went for things I didn’t want but might never be able to have again – pear and basil or something (I should have gone for chocolate). We came back the following week for my daughter, who by then had narrowed it down to her top twenty possible flavours.

Back with music, we live in an incredible time. The vast majority of the world’s music, all that has ever been recorded, is available to me and my family, any time we want it. Yet it feels far less satisfying than that trip to HMV or Vinyl Vault. This week I have been sitting, staring at my Spotify screen, keen to discover some new music but having no idea how to go about finding it.

It makes me recommendations, of course (and now they’re powered by AI - gasp!), but they seem more driven by acts it wants to promote than by the truckloads of data it has undoubtedly collected from me. I can’t trust it. Although to be fair, if it sees that on an average day I have followed some Hans Zimmer movie soundtracks with some 90s indie, then a couple of hours of ambient and the occasional 80s pop classic, interspersed with podcasts about running, self-improvement and board games, the algorithm may too wonder where to start in recommending what I should listen to next. Ha – tiny win for the human.

I used to rely on the radio, or Q magazine to get the latest hotness. For several years I subscribed to eMusic, which at the time (2008-2012ish) was a huge repository of mostly niche music that you could download based on a tracks-per-month subscription. But, critically, it also had a good selection of written articles, almost a magazine in itself built in to the website, through which you could discover new acts, new releases and forgotten gems.

Or, more practically, I would go into the actual record shops and see what they had on the new releases shelf, and talk to the staff and see what they recommended.

If the 1980s means of finding new music were the way it worked today, it would probably be challenged as a near-monopoly – the powerhouses of Top of The Pops, Radio 1, Smash Hits and HMV shaped a great deal of my adolescent music tastes, and a fair proportion of what makes it into the kitchen even today. But it meant you knew where to go.

From what I can understand from my kids, when they very occasionally share something about their day, they do still talk about music and share tips at school. Most of what they discover comes from songs featured on videos, or that are affiliated with some kind of show.

But I guess it’s not that different – however wide or narrow the funnel, there has to be a selection of music that is the most popular that week or month, and to be fair to today’s youth it’s not as if they’re all listening to the same stuff. So the music diversity apocalypse, where we are all served the same homogenous, over-sponsored tripe, may have been averted for now. Maybe The Algorithm won’t have it all its own way.

And it’s encouraging to know that I dislike the garbage seeping from Radio 1 today just as much as my parents did in the 1980s (what are they even singing about, I can’t hear the lyrics?). Some things never change.

So what I’m going to do is walk down to HMV this weekend and buy an actual physical album (assuming that CDs are still a thing) by a band or artist I’m interested in, and enjoy the walk home while reading the sleeve notes and then playing it on some kind of music-playing device. I’m smiling just thinking about it.

And it’s pay day – so do your own local record shop a favour this week.